Cognitive impairment is the hallmark symptom of Alzheimer’s disease (AD); however, neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), including psychosis, agitation and mood disturbances, are common not only in AD but also in Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal dementia and vascular dementia.1–5

Psychotic symptoms have been reported to be present in 12–74% of patients with AD, with a median prevalence of 41%.6 Typically, depressive symptoms develop first, often many months before a diagnosis of AD is made, while agitation generally presents in the months to years following a diagnosis. Paranoia may appear earlier than other psychotic symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinations, which tend to present after the diagnosis.7 Patients with AD and psychosis (ADP) typically suffer from delusions that are less bizarre compared with those in schizophrenia, which are often paranoid in nature or involve the belief that a deceased individual is still alive. Misidentification delusions, such as the belief that a family member has been replaced (Capgras syndrome), are common. Hallucinations are almost always visual; however, auditory hallucinations may also be present.8,9

Studies investigating the cause of psychotic symptoms in AD seem to suggest a multifactorial aetiology. There appears to be a genetic link, and a genome-wide association study in 2021 identified specific alleles that show a predisposition to the development of ADP, including apolipoprotein E ε4.10,11 Notably, psychotic symptoms are strongly associated with dementia with Lewy bodies, and a post-mortem neuropathological study of clinically diagnosed patients with presumed AD has implicated Lewy body pathology, rather than amyloid pathology, as a risk factor for the development of psychotic symptoms.12–14 However, this linkage does not appear to be absolute, as psychotic symptoms are still observed in patients with AD without confirmed Lewy body pathology.15

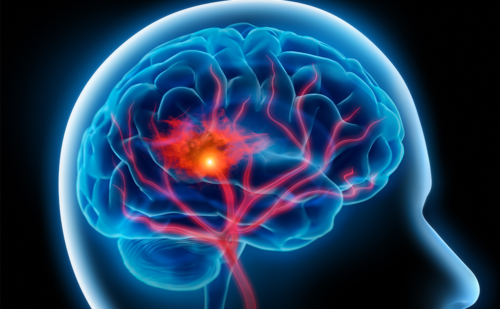

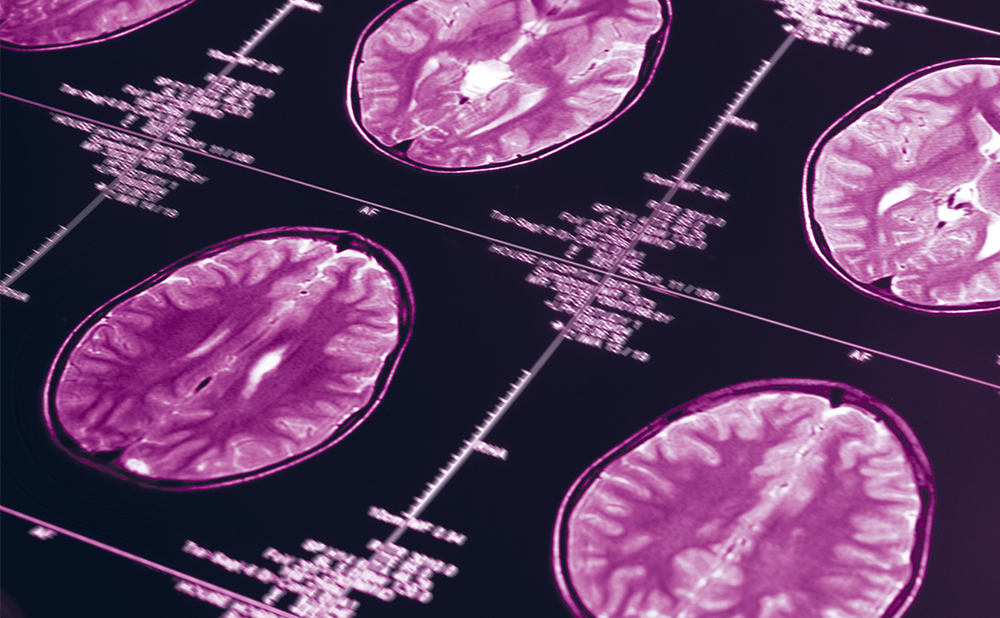

Neuroimaging studies have attempted to elucidate specific regions of the brain associated with ADP. Atrophy of the right hippocampus and reduced parahippocampal volume have been associated with psychotic symptoms.16,17 [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) studies have reported hypometabolism of the right insula, right orbitofrontal, right lateral frontal and bilateral temporal regions as being associated with the development of psychotic symptoms in AD.18,19 Epigenetically, ADP has been associated with hypomethylation of specific genes, including TBX15 and WT1, in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, superior temporal gyri and entorhinal cortex. Notably, hypomethylation of ASM3T is an overlapping feature between individuals with ADP and schizophrenia.20 [11C]Raclopride PET imaging has indicated that increased striatal D2/D3 receptor availability is present in patients with AD and delusions, suggesting that dopamine and dopamine receptor regulation may also play a role.21

The presence of psychotic symptoms in AD is associated with poorer outcomes for both the patient (worse quality of life, greater chance of institutionalization, greater functional impairment and accelerated mortality) and their caregivers (increased burden, stress and depression).22–26

Despite the significant prevalence and burden of psychotic symptoms in AD, their management remains challenging. In the following sections, we discuss current treatment options and novel targets currently under investigation.

Non-pharmacological management

As a principle, non-pharmacological approaches should be the primary tool in the attempted management of NPS of AD, including psychosis, according to a 2019 international consensus panel, along with an assessment of possible underlying causes and pharmacological treatment, if indicated.23 A reduction in polypharmacy, particularly the use of drugs with anticholinergic properties, should be strived for, as these have been shown to significantly increase the risk of developing ADP.27

Specific behavioural interventions and environmental modifications for the management of ADP have not been rigorously studied, and while there have been trials examining specific interventions for the management of agitation and aggression, the resulting evidence has been of low strength.28 However, anecdotal evidence suggests that environmental modifications, such as reducing clutter and noise, cues to maintain orientation and optimizing lighting, may be beneficial to some patients.29 One prospective cohort study showed that a programme of music therapy, orientation training, and art and physical activities was linked to a decrease in delusions, hallucinations and agitation.30 While not studied specifically in the context of ADP, it has been observed that patients with Parkinson’s disease often develop their own coping mechanisms for dealing with symptoms of psychosis, such as visual diversion or receiving reassurance from family members or caregivers that the hallucinations or delusions are not real.31 Prior to treatment, if an underlying medical cause has been ruled out, it is possible that psychotic symptoms may not need to be treated as long as they are not distressing to the patient.32

Non-pharmacological interventions may also be targeted towards caregivers, such as the development of coping skills or support groups, and have been shown to be effective in improving caregiver symptoms, even if the level of burden is unchanged.33 Improving caregiver-related outcomes is associated with improved patient outcomes, such as the ability to continue living in the community.34

Current pharmacological strategies

Currently, there are no medications with specific US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications for ADP. Once it has been determined that psychotic symptoms are not due to an underlying reversible condition and are impacting the quality of life of patients or caregivers, treatment generally consists of a second-generation (atypical) anti-psychotic.

The CATIE-AD (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness–Alzheimer’s Disease; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00015548) trial was a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial investigating the effects of the atypical anti-psychotics olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone compared with placebo on psychiatric and behavioural symptoms in patients with AD.35 On measures of psychosis, risperidone was the only medication that showed an improvement compared with placebo. Results also showed no significant changes in cognition or quality of life between groups and worsening functional skills in the olanzapine group. A 2006 meta analysis on the effect of atypical anti-psychotics to treat delusions and behavioural symptoms in AD and other dementias similarly offered modest support for the use of risperidone or aripiprazole but not for olanzapine. Adverse events were noted to include somnolence, urinary tract infections, incontinence, extrapyramidal symptoms, worsening cognition, an increased risk of cerebrovascular events and increased mortality.36 Increased all-cause mortality is a well-known complication in the treatment of older adult individuals with both typical and atypical anti-psychotics. An 11-year retrospective case–control study found that haloperidol, risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine increased mortality risk by 3.8%, 3.7%, 2.5% and 2.0%, respectively.37

A 2019 meta-analysis of 17 studies examined the effect of aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone versus placebo on effectiveness for the treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.38 Impact on psychotic symptoms was not explicitly studied; however, results indicated that across different outcomes, quetiapine, aripiprazole and risperidone were each modestly effective to varying degrees, while olanzapine was not. Aripiprazole showed the safest side effect profile.

Careful consideration of the side effects of anti-psychotic medications is essential for this population. Older adults with pre-existing diabetes are at an increased risk of hospitalization due to hyperglycaemia after the initiation of a typical or atypical anti-psychotic medication.39 Patients with gait difficulty may be more likely to fall if they develop orthostasis or extrapyramidal side effects.29

Of note, while not specifically approved for the treatment of ADP, cholinesterase inhibitors have been used for the management of NPS in AD. A 2023 meta-analysis showed a significant decrease in hallucinations and delusions among trial participants with AD; however, the effect size was small.40 Research focused specifically on the effect of cholinesterase inhibitors on ADP is sparse; however, systematic reviews have shown a significant correlation between cholinesterase inhibitor use and a reduction in overall NPS in patients with AD.41,42

Possible novel treatments

As described earlier, current pharmaceutical options for the management of ADP present specific challenges and drawbacks. Given this, several innovative strategies are under investigation to address these complications.

While currently available anti-psychotic medications target dopamine receptors, KarXT (xanomeline–trospium; Karuna Therapeutics, Boston, MA, USA) is a combination medication made up of the selective M1 and M4 muscarinic receptor agonist xanomeline and the peripheral muscarinic antagonist trospium chloride, a quaternary amine that does not cross the blood–brain barrier.43–45 Xanomeline alone has previously been shown to have a significant effect on treating both cognitive and behavioural symptoms of AD, including psychosis. However, a large percentage of patients experienced intolerable cholinergic side effects.46 KarXT has recently shown effectiveness in the management of symptoms of schizophrenia in the phase III EMERGENT-2 (A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-blind, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled, Multicenter Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of KarXT in Acutely Psychotic Hospitalized Adults With DSM-5 Schizophrenia; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04659161) trial and is currently undergoing similar investigation in the phase III ADEPT-2 (A Study to Assess Efficacy and Safety of KarXT for the Treatment of Psychosis Associated With Alzheimer’s Disease; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06126224) trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study specifically evaluating its efficacy on ADP in patients diagnosed with mild-to-severe AD.47,48 Notably, Karuna Therapeutics was recently acquired by Bristol Myers Squibb with the intention of bringing KarXT to market for ADP in addition to schizophrenia.49 Similarly, ML-007/PAC (MapLight Therapeutics, Palo Alto, CA, USA), a combined M1 and M4 muscarinic receptor agonist and a peripherally acting cholinergic antagonist, is currently undergoing phase I clinical trials, with phase II trials planned.50

Pimavanserin is a selective 5-HT2A-inverse agonist and antagonist with no appreciable affinity for dopaminergic, muscarinic, histaminergic or adrenergic receptors. It has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease.51 The phase III HARMONY (A Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Relapse Prevention Study of Pimavanserin for the Treatment of Hallucinations and Delusions Associated With Dementia-related Psychosis; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03325556) trial was a randomized discontinuation trial to study the effect of pimavanserin on the treatment of psychotic symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, AD, frontotemporal dementia or vascular dementia. Relapse of psychosis was found to be significantly decreased in the treatment group, and the trial was halted early after reaching the efficacy endpoint.52 The data were submitted to the FDA for an indication for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis but was denied due to concerns that the effect was primarily driven by the results in patients with Parkinson’s disease.53

The CITAD (A Multi-center Randomized Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial Study of Citalopram for the Treatment of Agitation in Alzheimer’s Disease; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00898807) trial studied the effects of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram versus placebo in patients with AD and found improvements in both the primary outcome of agitation and the secondary outcome of delusions (but not hallucinations). Specifically, agitation was improved in patients with the HTR2A and HTR2C polymorphisms. However, specific genetic analysis for psychosis was not performed. Notably, the treatment group was also found to have significantly increased QT prolongation and worsening cognition compared with the control group.54–57 As the R-enantiomer of the racemic mixture of citalopram is primarily responsible for the QT prolongation, a phase III trial is currently ongoing to study the effect of the S-enantiomer, escitalopram, on agitation in ADP as a secondary outcome.58

The Lit-AD (Treatment of Psychosis and Agitation in Alzheimer’s Disease; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02129348) trial studied low-dose lithium as a treatment for agitation with or without psychosis in AD and found significant improvements in both delusions (but not hallucinations) and irritability.59,60

A 2019 retrospective study found that patients with AD who had previously taken supplemental vitamin D had a delayed onset of psychotic symptoms compared with those who had not. This finding is consistent with previous studies suggesting an association between vitamin D deficiency and psychotic disorders. However, this effect has not been further studied in prospective trials.61–63

Applying deep learning models to electronic medical records is one area that may help develop new therapeutic strategies for managing ADP. One study examined patient records to find medications or supplements that had either a beneficial (vitamin D, quetiapine, duloxetine and memantine) or hazardous (warfarin, allopurinol, metoclopramide and fluconazole) association with the development of ADP.64 While these studies are not substitutes for randomized controlled trials, they can be highly useful in helping identify previously overlooked pharmacological targets.

Conclusion and recommendations

The presence of psychotic symptoms in patients with AD presents significant challenges for the treatment and well-being of not only the directly affected individuals but also caregivers. Approximately 40% of individuals with AD will develop psychotic symptoms, which are associated with decreased quality of life, increased mortality and increased caregiver burden. The treatment of these symptoms with currently available anti-psychotic medications is complicated by substantial risks in older adults, including worsening cognition and increased mortality. This highlights the need for further study into tailored management of psychotic symptoms in this specific population.

Ongoing research into targeting central muscarinic pathways aims to balance efficacy and safety, highlighted by the current phase III trial of KarXT. The non-dopaminergic anti-psychotic pimavanserin, which has already been approved for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease, also merits further testing, specifically in the AD population. While these represent promising steps forward, the scale and severity of the challenges posed by the management of ADP warrant continued study into other possible novel therapeutic targets.

In the meantime, currently available pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments should continue to be optimized for this population. Given the potential risks of anti-psychotic medications, more rigorous studies into the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions are strongly warranted. The available literature from clinical trials suggests that if an atypical anti-psychotic must be used, risperidone or aripiprazole is likely to be the most effective.